The urban legends of my childhood all involved men. Men in the backseats of cars. Men with hooks slashing. Men pretending to be cops. And men calling babysitters.

I was a child in the 80s and a teenager in the 90s. These were years of an explosion of horror films from The Shining to A Nightmare on Elm Street to Scream. But the scariest aspect of these scary movies for me is the time in which they were set: the time I grew up—years in which we were terrorized by misinformation and silence.

In films that bookend this era, When a Stranger Calls and its 1993 sequel When a Stranger Calls Back, much of the fear is about isolation. 1979’s When a Stranger Calls starred Carol Kane as a babysitter who receives the legendary “Have you checked the children?” call, only to be told by police that the call is coming from inside the house. Both movies start with babysitters getting calls, when the only phones are landlines.

There’s no caller ID, no *69 even. I remember our rural Ohio town getting 911 when I was in middle school. It was a big deal; we had an assembly about it.

I’m not sure I can emphasize how alone we were. So many times I rode with friends into the night, to a party, or a friend of a friend’s, or a band playing in a garage or a cornfield somewhere, not knowing how I was going to get home. Not knowing exactly where I was. Not knowing if I would be able to find a payphone, or if anyone would pick up at my house. If someone’s older brother or sister had wheels and could be trusted. I was a responsible kid, but it was hard when rides were out of my control. I remember my parents driving around looking for me.

When my father broke his arm as a kid, he was alone, miles from home, in the country. He had to ride his bike, one-handed, an hour into town for help.

My family’s first experience with cell phones came when my mother’s car broke down. She was alone, on another country road. A van stopped. The stranger who was driving said, “Well, get in.” And like a girl in a horror film, she did. To her surprise, there was a phone inside the van. She got home safely.

Lack of connection isn’t the only peril for the women in both Stranger Calls movies. They’re disbelieved, simply because of who they are. Kane’s character in the first film calls the police only to be told initially the caller was “probably just some weirdo.” The cop who talks to her recommends she whistle the next time the threatening man calls back, to annoy him, in a ploy that echoes my first year of college when all the girls in my dorm were given rape whistles. It was the only sexual violence or consent information we received.

It’s one thing to endure the misogynistic cops on Netflix’s 2019 series Unbelievable, based on a true serial rapist case, knowing eventually the survivors will be redeemed—or at least, believed. It’s another to watch a movie from the 90s where the sole woman in the room says about the victim: “I believe her.” And the three (male) cops are shocked: “What?”

When that woman—Kane’s character, who has become a college dean by the time of When a Stranger Calls Back —says she knows about trauma experienced by the victim, a cop says: “What are you, clairvoyant?” She explains that she has files.

And this is the last time we see cops: stalking cases aren’t really high on the priority list in the 90s. In my own experience of that time, there was no justice and no hope of justice. What could we do?

When a man exposed himself to me, the responding officer told me to get a knife. That same year, a friend across town saw a man peeping at her through her windows. When she told neighbors, she discovered multiple women had had the same experience. When the neighbors reported it, they were told simply: “We normally recommend street justice in these cases.”

Police procedural is scary in the 90s. It will take three days for the aforementioned files to arrive in When a Stranger Calls Back. Kane and a private investigator both handle evidence without gloves. The PI character barges his way, under false pretenses, into the apartment of a female witness who lives alone. Even he, the only supportive male character, starts to doubt the survivor.

Sexual violence is the shadow that hangs over these films, as it hangs over most horror movies with women or girls, but the motive for the crimes is never delved into at all, sexual or otherwise. The viewer is told that the boy and girl children from the first movie were killed horrifically, and that the children from the second disappeared.

But the killer also stalks grown women, along with teen girl babysitters—and the perpetrator, when unmasked, has an unmistakable aura of queerness, a familiar trope of the maybe-gay man who murders in such films as Psycho and Seven. The effeminate man must be scary because he defies convention. This character, seen in movies from The Lost Boys to Hellraiser, has been referred to as “the monstrous queer”—and it’s no coincidence that this trope, with its accompanying homophobia and transphobia, dominated in a time of great conservatism and AIDS.

People talk a lot about the satanic panic of the 80s—but what about the sex panic, another destructive moral fervor?

As children of the 80s, we were told that if we had sex, we would get AIDS and die. Maybe get pregnant, then get AIDS, then die. We were told transmission most commonly came from sex, but we were still confused about what that was. Better not to do anything. On the playground, when a classmate fell and there was blood, even just a skinned knee, we saw teachers’ alarm and reluctance to help the child. Same with menstruation in the bathroom.

We were told about condoms in school though we had no access to them, but not birth control pills, certainly not the female condom. A friend said her older brother had put a cat down his pants and few months later, the cat gave birth to kittens. As children, there was no way to fact check that, nor when a high school girl told me she had had to have her stomach pumped because she had given so many blow jobs. There was no google search to quell our nightmares. We had to go by peer information, and what we were given in school and in often-outdated books, which was not great. I remember reading in a book that sex was a hug. When my best friend hugged me the next morning, I was distraught.

We learned euphemisms—not the correct names—for body parts, which is actually dangerous for children. We learned to be ashamed of our bodies and what might be happening with them. We learned the world was out to get us, and it was.

What saved me from the misinformation and repression of my childhood was the fact that I knew gay men from performing in community theatre. Several of my friends were diagnosed with HIV in those early years of AIDS. Two people I cared deeply about would die from complications of the disease, and one lives with it now.

I held a man who had AIDS in my arms when I was a teenager. He fell, tripped backstage in the theatre where we were working on a show together and I caught him. Less than a year later, he was dead. And I lived. That was a lot of pressure, to live. To live at a time when others are dying, simply for the sin of being alive.

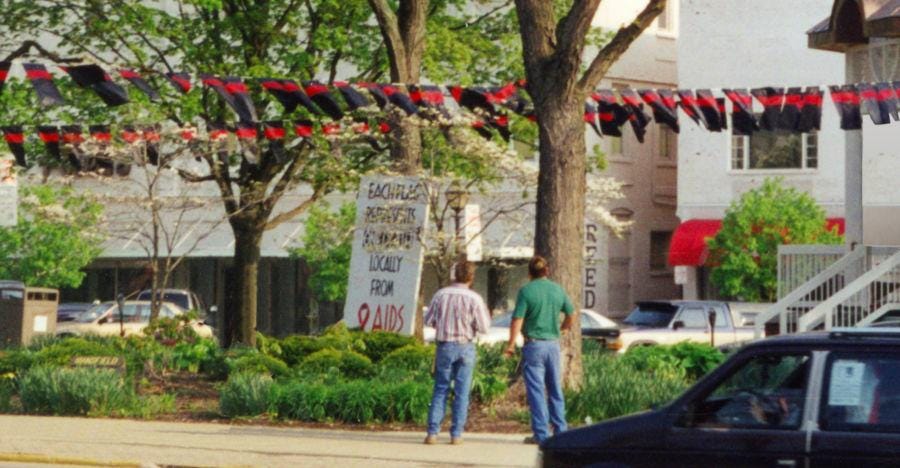

My Ohio hometown with a 2000 display of flags representing each local (known) death from complications of HIV/AIDS.

The ending of When a Stranger Calls Back is pretty bleak. They get the guy, but the cost to women is extreme. The movie doesn’t have the gore of present-day horror films but is no less horrific, not just with psychological torture, but with gender violence, including the beating of a comatose girl in her hospital bed. “What choice does she have? What choice do any of us have?” Kane says in the film.

I see a lot of nostalgia happening now for the 80s and 90s. Maybe Stranger Things helped kick this off, maybe it’s a deeper reaching back to a simplicity that predates the horror-of-now: how difficult and precarious the world is, exactly how much terrible information we realize about it, which is a lot.

But the scariest aspect of Stranger Things 3 for me was that nostalgia I felt watching it—a deep longing for the time when no one could reach me, when I didn’t know anything.

The clothes are back from that time, of course; the clothes are always coming back. I’m excited about the combat boots. I held onto mine, all these years.

But what I hope never returns from the 80s and 90s is the silence, the deep fear, confusion, and isolation that gripped me and everyone I knew growing up, especially the girls. The call was coming from inside the house. And we had to answer it. And tell it no.