When I was nineteen, my college advisor pushed a VHS copy of The Red Shoes, the 1948 film about a ballerina, across the desk to me. “Men are going to make you choose,” he said.

I didn’t understand. I was dating someone, a fiction writing student who was about to get really, really mad at me when I won a writing contest he had also entered, in a different genre category. It feels like a betrayal, he said.

Was that what my advisor meant?

Or was it the night before my PhD defense, when my then-husband fought with me, saying over and over he didn’t understand what was in it for him, this me obtaining an advanced degree thing?

In The Red Shoes, the main character, a ballet dancer, is forced to choose between her career and the love of a composer—her art or her heart, basically. She can’t give enough to either to make them both work, not in the confines of the world men have made.

What was I going to be forced to do? I should have asked my advisor. What was the right choice? How did he know? I was a teenager. I had just cut my hair. For our honors class, I wrote an opera.

I think he saw someone in me who was not going to be content unless they made stuff, not satisfied with the world as it was. And to have anything approaching more, especially as a person who is not a man, requires a whole hell of a lot of time.

Throughout my twenties and early thirties, I gave up time. I didn’t realize it was a precious resource. And finite. There would come a point when it would be involuntary, my losing it. As a young woman, I gave up time willingly. I gave up time to getting ready. I gave up time to a man who couldn’t bring himself to say he loved me. I gave it up to standing in the corner at parties. To going to readings by bad writers, who were almost always white and men. To cooking meals no one appreciated. And to cleaning. So much time lost to cleaning, straightening up. Making everything, including myself, look nice. I gave up time I could have spent making art. I lost it.

So the choice after all was me. Me—or everything.

To ask an artist to choose a man over her work is asking her to choose a man over her life. Or her love over her love. Which, I mean … we do all the time, especially to mothers. But it’s not much of a selection. And it’s not one that men are forced to make.

It’s been awhile since I’ve read the book, and to be honest, Little Women is not my favorite. Unsurprisingly, maybe, I prefer Alcott’s book Work. One thing I always loved about Little Women, though, is that the sisters are all artists.

Throughout the book and film versions, Jo and Amy are the clear competitors. Meg takes herself out of artistic competition by marrying, giving birth to twins, and giving up such things as theatre. Beth is taken out by illness, terribly. But Jo and Amy make it a long way.

Amy has both the artistic leanings of her older sister, the writer Jo, and the added bonus/burden of beauty, an attribute she cultivates, constantly pinching her own nose to try to make it smaller. She’s told as a child that she alone must save the family, and save it through marriage.

No pressure.

That was another thing a man told me, my driver’s ed instructor who lectured me, trapped in the front seat as we teetered around the country roads, “You want to be an artist? Marry a rich old man.”

I didn’t know back then that some men love a wild thing just to keep it in a cage.

I cried at Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. But I didn’t like any of the concessions away from an artistic life, of which I felt there were many. I didn’t like that the girls’ mother, Marmee, brings Jo a tray of food while Jo is intently working—though what I wouldn’t give to have food fixed, brought to me, and taken away so that I could continue my work. Still, I couldn’t help thinking: What about Marmee’s work?

In an oft-quoted line in the film taken directly from Alcott’s journals, Marmee says she is angry every single day. But about … what? What specifically did she give up? A career in social work, like Alcott’s own mother, or her own artistic yearnings? Or is she angry about having to do everything alone, as her husband—a character I’ve never been fond of, or really noticed at all (oh, he’s still alive?)—enlisted away from home?

Amy stops making art. And artists don’t do that. They just don’t, unless they’re physically forced to by illness, poverty, abuse, which doesn’t happen to Amy.

Maybe this means, as generations have insisted, Amy isn’t a “real” artist. Or maybe she is forced to stop by the pressures of being a pretty woman. Maybe she never had a chance, and the failings of the character are also really the failings of her family, sexism, the world. What if, after all, Amy was the better artist? What if Meg was? What if Marmee was?

I liked Little Women. But something that bothered me on a deeper level was the whiteness of it all. I complained to my partner: why do all the actresses have to be white? He said: “Maybe only white women would have a choice.”

We love Jo because she makes it. We hate Amy because she gives up. But it’s a privilege even to have the option.

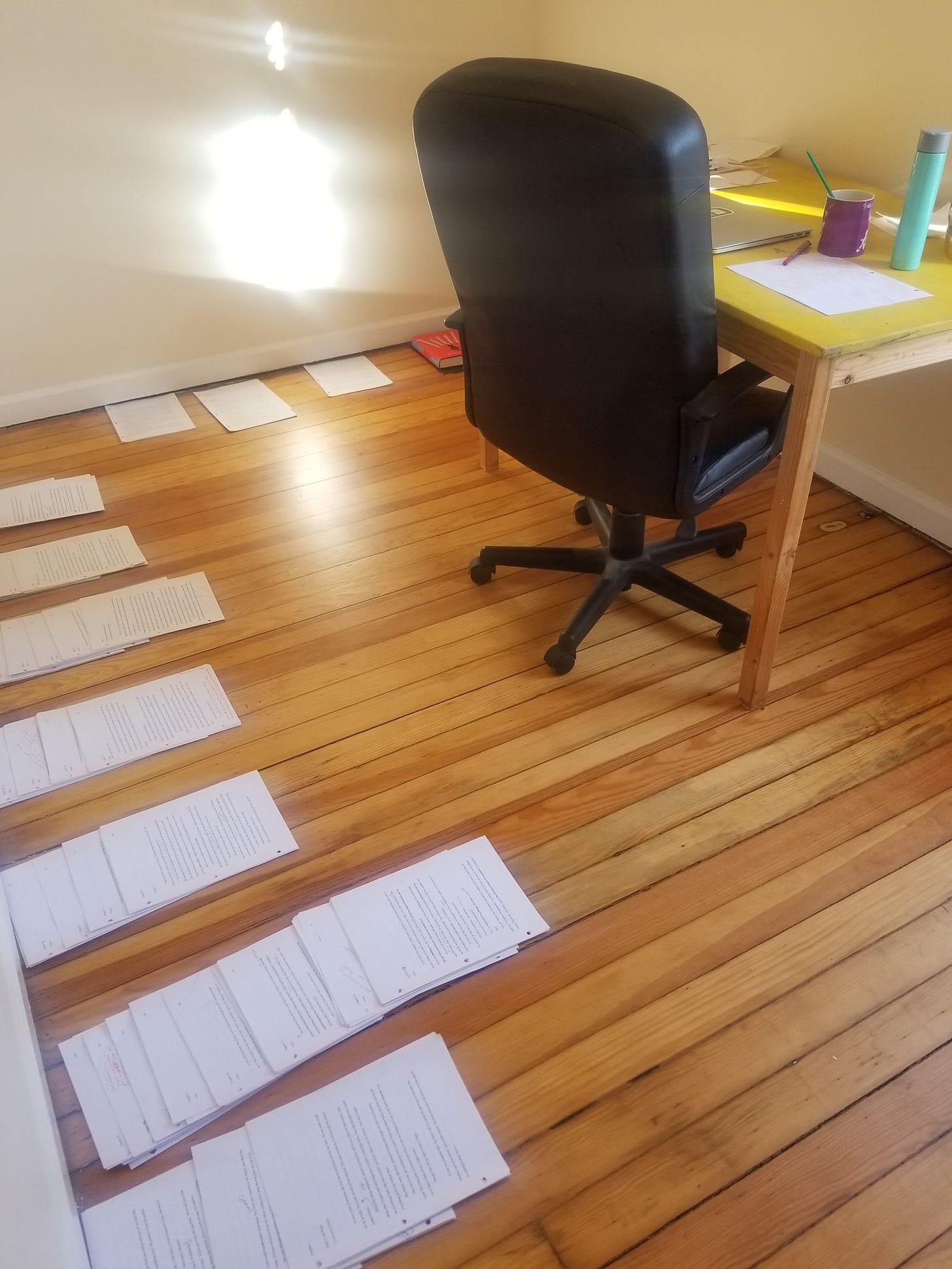

My partner and I saw Little Women together, and he will be the first to tell you he cried too, especially at the scene where Jo lays her manuscript out on the floor. Because upstairs at home, in a small back room he protects, forbidding anyone else from using, or leaving their stuff (or playing) in—I was doing the same thing.

(hey I have a book coming out!)

Enjoyed this. Thanks for writing it. The screenshot made me laugh.

I do think artists sometimes stop making art—not just illness (unless you count existential malaise) but having kids and being overwhelmed, getting discouraged, feeling like if you haven’t make it by X age it’s never going to happen. I don’t think these people are any less “real artists.”

I stopped writing for awhile. I was depressed and not getting anywhere. I had kids and put it aside. That felt really bad and I came back to it. But I don’t think I stopped being “an artist” when I wasn’t making art. I tried taking pictures, I still read, I still thought about things in my way.

That’s all. Thanks!